During the final years of WWII and after the war ended in 1945, approximately 12 million refugees and expellees migrated to a war-torn Germany where the living standards were low and the economy shattered. Many of these refugees had relatives whose ancestors were German. Johanna Ditter was one of them. Her mother’s ancestors migrated to Russia in 1862.

The conditions refugees faced more than 70 years ago have a stark resemblance to what refugees from war-inflicted countries, such as Syria, making their way to Germany and other European countries have to endure nowadays. In 2019, roughly over 110,000 first-time asylum claims were filed in Germany. The largest number of asylum applications, approximately 26 thousand, were Syrian nationals.

In the spring of 1942, the German troops had invaded large areas of the Soviet Union and captured Ukraine, Belarus, and the Baltic republics. The Battle of Stalingrad (which is now Volgograd), which began in August 1942, was meant to bring southern parts of the Soviet Union under German control. The German troops were defeated in February 1943. This defeat destroyed the image of an invincible Germany Hitler had tried to uphold, marking a turning point in WWII. Germany couldn’t avert its impending doom anymore.

When German troops were in retreat after the defeat at Stalingrad, a mass expulsion of ethnic Germans throughout the region of the Soviet Union initiated. Since Ditter’s mother’s side of the family was ethnically German, they were afraid of what might happen to them if they remained in the country.

“It was in 1943. We drove through burning forests, we didn’t use the main roads, we used the small side roads, because the military was on the main roads shooting at people and vehicles. Everyone on their way to Germany who was caught fleeing the country was shot by the Russians.

My father had two horses pulling our carriage. You could think of it like a hay cart with wooden rods. And he covered all of us with a tarp so nothing would happen to us in case burning tree limbs fell or something like that. But I was curious of course and lifted the tarp here and there because I wanted to see where we were going. And I saw dead soldiers laying by the side of the road. I saw people without heads, I wish I hadn’t been that curious. [silence] Horrible. But we made it through. We went through Poland, Czech Republic, and all these countries on the way back from Russia to Germany.

When the war happened with Hitler, Hitler came all the way to Russia as well. The Russian wanted to keep everyone in the country, but we fled anyway. I was six and a half almost seven, and my sister Olga, your grandmother, was not even two. Her birthday was in November. It was Olga and me, our parents, a sister of my mom’s who also had three children, and our grandma of course. We all fled together.

Father, he was mute and deaf, but not from birth. His father was Ukrainian. When his accident happened a horse carriage came. My dad grew up with horses on the family farm. He was 15, somehow the horses were scared and about to bolt, but my father thought he could stop them. The horses went right over him and stomped on him, and he had a bunch of scars on his head and everywhere. Once he was getting healthy again they realized he couldn’t speak and also didn’t hear anymore.

As he got older, he met our mother, but she didn’t want to marry him. She thought her children would also be deaf and mute – which wasn’t the case because in his case it wasn’t hereditary. But father had a sister, a really nice one, and she spoke with mother and convinced her to marry him.

This was also unusual because back then Germans and Russians or Eastern Europeans didn’t mix. Russians totally opposed such a marriage. But it was different with our parents. Back then it wasn’t like it is nowadays. Nowadays deaf and mute people have agency and rights and can decide also when they have children and can raise those children, back then this wasn’t the case.

All refugees were brought to a refugee collection camp in Poland and the German soldiers greeted the refugees right away. They removed fleas and lice and what not – a bad story. We had to stop two times. If you imagine today the refugees that come on the water, it was pretty similar, just that we didn’t come over the ocean.

For food there was one slice of bread for adults and a bit of porridge for the children or soup. Because my Olga was so little I had a little drinking cup, so I went to get porridge and ate it and went again to get more. They asked me who the second portion was for and I said: “It’s for my little sister, she’s still so small.” So they told me twice is ok, but I couldn’t come a third time.

And the slice of bread mother got, she mostly didn’t eat, because she kept it for me because I was always hungry. Father – they took him right away. The German soldiers took all the men. They didn’t even ask! They just took him. All they needed was men who could shoot, it didn’t matter if he was deaf or mute. They just wanted him there and if he were to get killed – bad luck. Hitler didn’t care about any of that. If he had opposed they would have killed him on the spot. My father was with the Germans. When we were in Poland they took him. The Germans were already in retreat. And they took in every extra soldier they could to help Hitler win. Nobody knew where they sent him. They just loaded him on the military truck and took him. And after that you didn’t know anything – was he alive, was he dead. Hitler wanted to win!

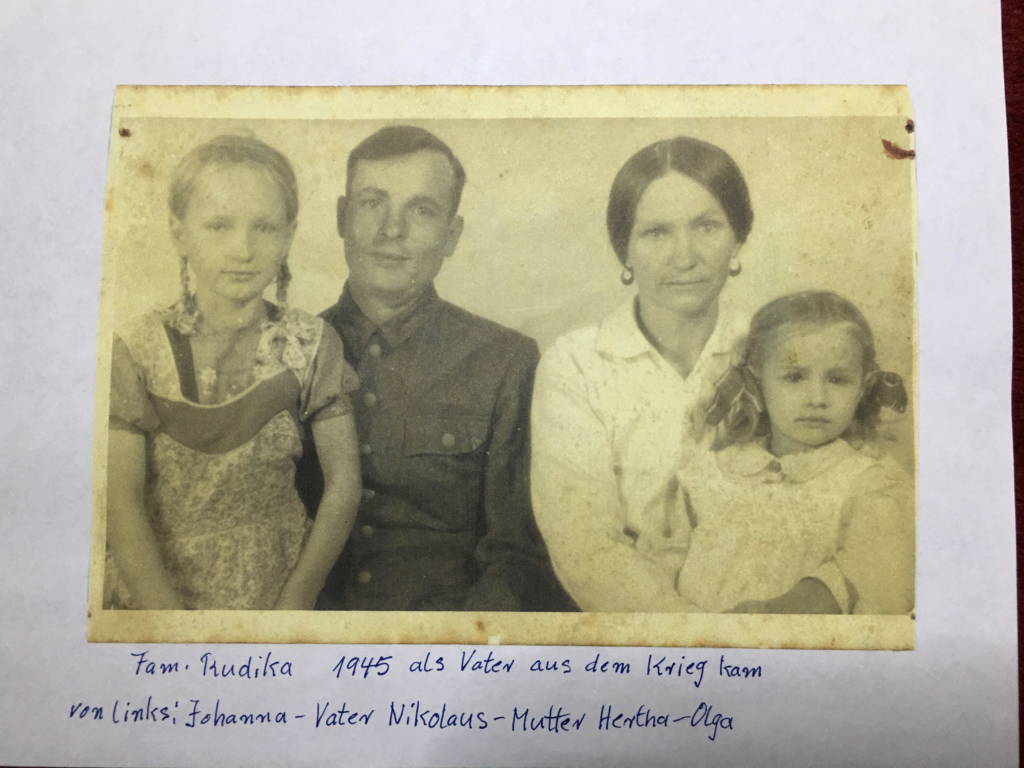

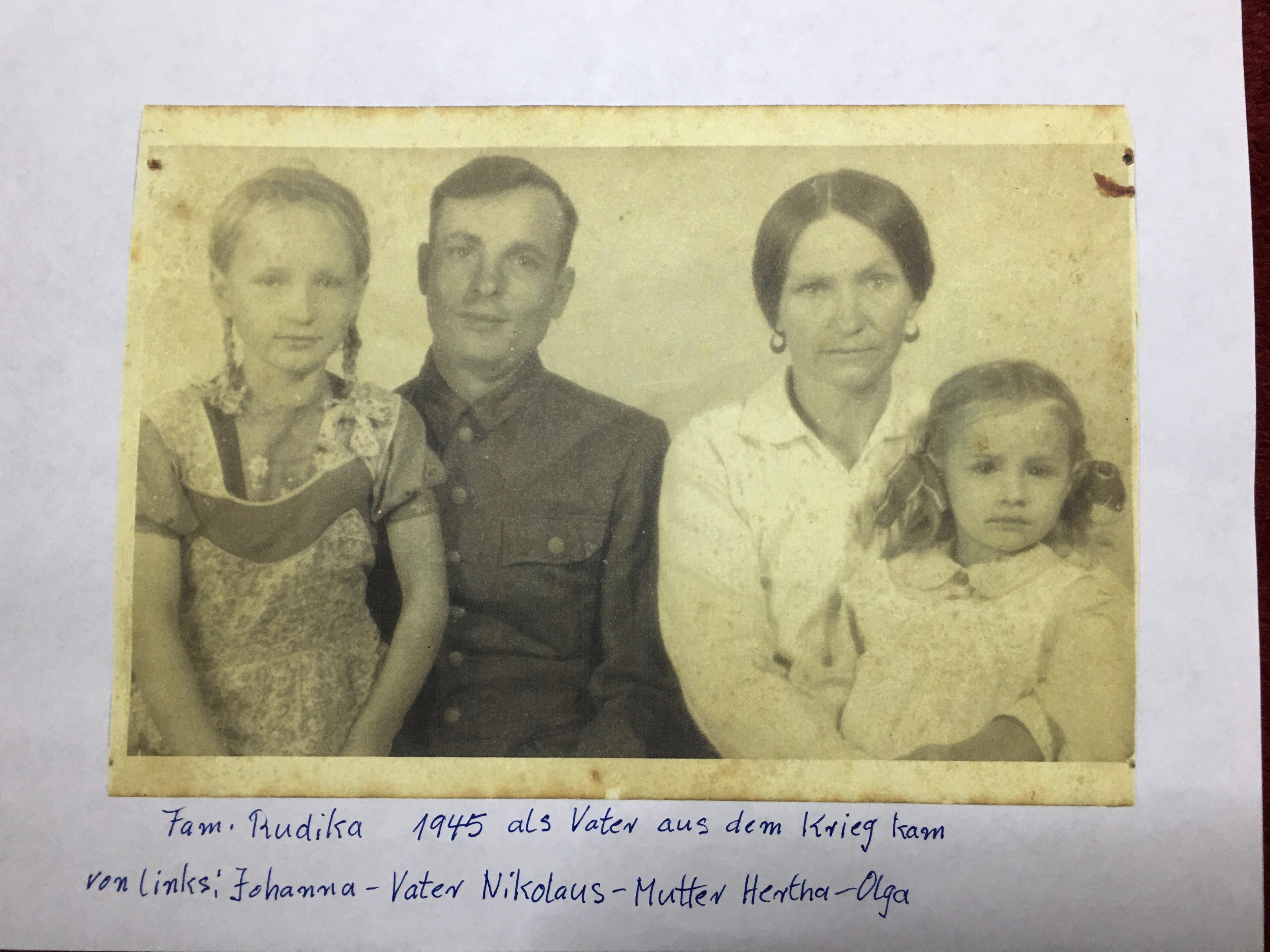

When Hitler lost it was 1945, that’s when the war was over. And our father was able to write in Russian. How he ended up finding us – I can’t explain to you. I thought about it so many times. We were in a small town close to Wolfsburg. When the war was over our father found us. It must have been through the Red Cross and he probably wrote down his name and information about his family in Russian. And you have to consider, he didn’t hear, he didn’t speak, but he survived the war without any injuries. And he was gone for a year or so.

And all of the sudden he was back. They unloaded him at the village entry and he walked around the village and had to look for us. He came around June or July 45. It was cherry season.

When our father came home, mother was already really sick. She was working for one of the farmers and had to go to the hospital, where she got operated on. She had colon cancer. They couldn’t help her. They just sewed it back up. She wasn’t allowed to stay at the hospital because that’s where the wounded soldiers were. They needed that space for them. They put her in a sort of makeshift care facility. Father and I always went to see her on Sunday. We walked all the way from the farmer to where she was in Wolfsburg – 10 kilometers each way. They didn’t have a lot of food over there, so we brought food for a week from the farm – that’s how she was able to stay there.

Mother was there for 9 months, then she died, she passed away in 1946. She couldn’t see Olga, she was too small. She couldn’t walk 10 kilometers with us. That really hurt her. Then she said to me, because father was deaf and mute and didn’t have rights: “Watch over your little Olga.” I had to promise that to her. On the deathbed I had to promise her that I’d watch over my little Olga. Which I did, as good as I could as a 10-year-old child. We were six years apart.

Imagine how things went from there! The Americans, the British, the Russians and the French – the four powers had four zones. You weren’t allowed to travel between zones without authorization unless you went illegally. And we were in the British zone, Wolfsburg was part of the English zone. And here in Schwäbisch Gmünd was the American zone. And the farmer – he would have liked to keep our dad because he was a good worker, but mother wasn’t there, so the two children were obviously in the farmer’s way. Father couldn’t do anything and the farmer wanted to put us in an orphanage. But the Red Cross found one of our mother’s sisters, our aunt. She lived in Schwäbisch Gmünd.

That’s when the misery began. The first obstacle was: How would we get from the English zone to the American zone? You can only do it illegally, but you can’t get caught. So the aunt’s oldest son; she had six children of her own and was supposed to take us in as well! She lived in one of the refugee barracks. Her oldest son, no idea how he did it, but he came to Wolfsburg to get us and brought us over to the American zone.

It was one of those barracks for refugees close to a sports ground. It was sort of like a barn, the ceilings weren’t very high. We all had to sleep in a bed with two or three people.

We grew up in times of war. I didn’t even know when my birthday was. On my eighth birthday my mother made a cake for me in a tin can. She prepared the dough and baked a cake for me in one of the refugee centers we stayed at on our way. And I remember saying: “Oh wow what is that? I’ve never seen anything like it.” And she said: “It’s your birthday today.”

In the refugee barrack we had two rooms. One belonged to our aunt, the other one was for all of us children. That room was living room, kitchen and sleeping room at the same time. It was very crowded. We had a stove similar to those in the farms back then. You had to use wood or coal for those stoves, there was no gas or electricity. There was no yard.

And there we were. The aunt’s six children and us two – eight children, you’re too much in every corner. We weren’t doing well there. I was the oldest of the girls. She had me do all the chores – washing the laundry, doing the dishes and all that – I was her domestic servant. Olga was small, and also a very lively child and she wasn’t blonde! She had black hair like our father. And whenever she was a little energetic our aunt couldn’t take it and called her “Black witch.” So I told my aunt: “This is my sister and she has a name!” – but what can you do as a 12-year-old child, especially when she has six children of her own. We were unwanted.

She wanted to get rid of me. The Americans were looking for children to take to the United States. Because apparently there were people who wanted to adopt young refugee children. The Americans were very child-friendly. There was this lady in charge of the process. Coincidentally, I walked into the living room and my aunt is talking to this woman. And the woman says: “No, she’s already too old, but I could take the younger one.” So I said: “What is too old?” My aunt wanted to sell Olga to the Americans, they would have paid her. So I said: “My Olga stays here. Where I go my Olga goes as well. And alone she’s not going to go anywhere!”

So I got into a big argument with my aunt, but I was already used to a lot. I kept her here with me.

And my father – Oh lord, I’m telling you. You know he worked for another farmer in a village nearby. He loved working there and the people loved having him because he knew so much about farming and knew how to treat the horses. He received 25 DM (Deutsche Mark) every month for his work. He was provided a place to sleep and food. But it wasn’t enough for my aunt. Whenever we were on holiday from school she sent us to stay with our father on the farm. But even while we were staying with the farmer she still requested all the money from him.

The aunt’s oldest son worked in road construction in Göppingen. So they decided to get my father from the farmer and have him start working in road construction as well, so he’d make more money. Then they wanted my father to pay for a motorcycle for the son so the son could drive my father around. We had our way of communication, so I told him that it was a trick – that my cousin would drive around with the motorcycle and he’d sit at home. “There is no way this is going to happen,” I told my father.

The street they were working on was right next to a train track. My father had to use the restroom. Where would he go – there was no actual restroom. He went behind the train tracks to find a bush or something so nobody would watch him. So then he wants to walk back to his job and a train comes and he can’t hear the train. And the train signals and signals, but my father didn’t move out of the way. Of course the train tried to stop, but it was too late and it ran over him. It was the month of his 40th birthday. [silence]

I came home from work. My aunt said: “Food’s ready, come eat.” All of the sudden she was all friendly. So I sat down and she tells me: “Your dad is dead.” I was 15. I said: “I can’t believe that!” She explained to me what had happened. Then a police officer came to investigate what had happened, why he had been run over by the train. So my aunt tells them it was my fault! My fault! They asked me and I told them it was all a lie. They verified everything and I never heard from them again. My aunt thought if she told them it was my fault they’d take me away and put me in jail. She told them that we had an argument and that probably upset him. We didn’t have a fight, I just told him not to pay for the motorcycle. I told the police about all of that.

Today, thinking back, I think it might have been an easier life for us if we had just been sent to an orphanage. If you’re treated by your own relatives in such an awful way. With strangers it would have been a different situation. The only thing that kept me sane was the thought that God would punish her – Well, that never happened – God forgot about her, she was doing just fine.

Oftentimes, I was thinking about a way to end my life. I couldn’t take it anymore. If I hadn’t promised my mother that I’d watch over my Olga…And how can you expect that of a 10-year-old girl? But she didn’t have any other way. Later, when I was older, I realized that. She didn’t have any other way than to put me in charge of Olga. I don’t know what I would have done out of despair, leaving behind a small child. Olga wasn’t even five back then.

You know, I keep suppressing these memories. In the beginning, it almost made me sick. You just have to keep putting it behind you.

Eventually I had a boyfriend. My aunt found out of course. So I had to bring him over and they examined him. I was about 15 or 16 then. Then she told me to get married. And I said: “With what? I don’t have anything? With what could I possibly get married? And it’s way too early.” So she said: “You’re already an old cow, what are you thinking!” I can’t even tell you what all we had to suffer living with her.

Then I was 17 and she kept pressing me to get married. But my boyfriend Roland’s dad had an apartment. Back then it was hard to get an apartment. Getting married at a young age as we did you wouldn’t have found an apartment anyway, even if you had been able to pay for it. So Roland’s father said we could move in with him. I was already working. With 14 they kicked me out of school and made me go to work. And if you didn’t find a job you had to work as a maid for one of the farmers.

We said that I was expecting a child so they would allow the marriage. But before that you had to go to the public health department and have the man and the woman’s blood tested. If the blood wasn’t compatible, you weren’t allowed to get married. I don’t know how they figured out what was compatible and what wasn’t, but thankfully ours was compatible. Those were still laws back from when Hitler was in charge so no disabled children would be born.

And do you know when the child was actually born? Six years later! I was already married for six years then.

After I got married, my Olga was allowed to come over every weekend, but on Sundays she had to be back home at 7:30 pm at the latest. One Sunday we had friends over. It was getting a little late. She was already worried. At that time I might have been married for about three weeks. So I said, just tell her that we had visitors and explain the situation to her. But our aunt didn’t want to hear anything about it; she told her: “Go back to where you came from!”

So she came back to our apartment. She cried. Two of Roland’s friends were with us. One of them said: “What did your aunt say?! Go back to where you came from? Well if that’s the case, that’s exactly what we’re gonna do. You stay here with Johanna and the two of us will go and get the girl’s things.” So that’s what they did. She didn’t have a lot. They got all her clothes and everything. Then my Olga lived with us.

I was happy when I was married and my Olga was with me. That was a relief. That’s when things started getting better.

Your grandma also started working when she was 14 or 15. At work she met your grandfather Rudi. And one sunny day Roland wonders: “I don’t know what’s taking Olga so long today. I hope nothing has happened to her.” Normally, she would have been home long ago. But she didn’t show up. Then Roland was looking out of the window – nothing. Then all of the sudden she comes up the sidewalk very slowly and Roland says: “Oh wow! That’s Rudi, she’s coming up the street with Rudi Schweitzer!” – and Rudi was one of Roland’s cousins. It’s crazy how life plays out sometimes. The two of them met and found the loves of their lives. They got married in 1960. [silence]

You know – I really miss her, my Olga.”

Be First to Comment